Independence Day

- Oscar

- Organizations , Finland

- December 6, 2023

I started writing this post on December 6th, Finland’s Independence Day. This is my first one since relaunching my blog, and though I have republished some content in Spanish from my old site here , it was perhaps not a bad place to (re)start: one of the topics that has been the most in my mind in the last few years has been that of organizations. In particular, I have been reflecting on the role of work, the organizations many of us spend the majority of our waking hours in, and the ways in which they enable or prevent people from living fulfilling lives. I hope to touch on this topic in more detail as I start writing again. But today, while Finland celebrates its independence, I just want to leave some ideas and questions on the tensions between the ways we accept or reject claims made by one particular type of organization, States, over their subjects (us), and how we seem to hold a different set of principles and beliefs when in comes to other types of organizations, such as business, NGOs or religious institutions.

·•·States are political organizations, instruments to achieve order over a territory by a “monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force”1. The relation between State and force includes the concept of legitimacy, so it is not so much about “brute” or “raw” force (the external means) only, but a combination between the material means for violence with the symbolic mechanisms (inner justifications) that make it acceptable by those thus dominated. The conditions that gave rise to Finland as a State show how the deterioration of the Russian-based order and its legitimacy played a key role in providing the opportunity for a new one, but not without a deep struggle first, and the need for new justifications and concessions that followed.

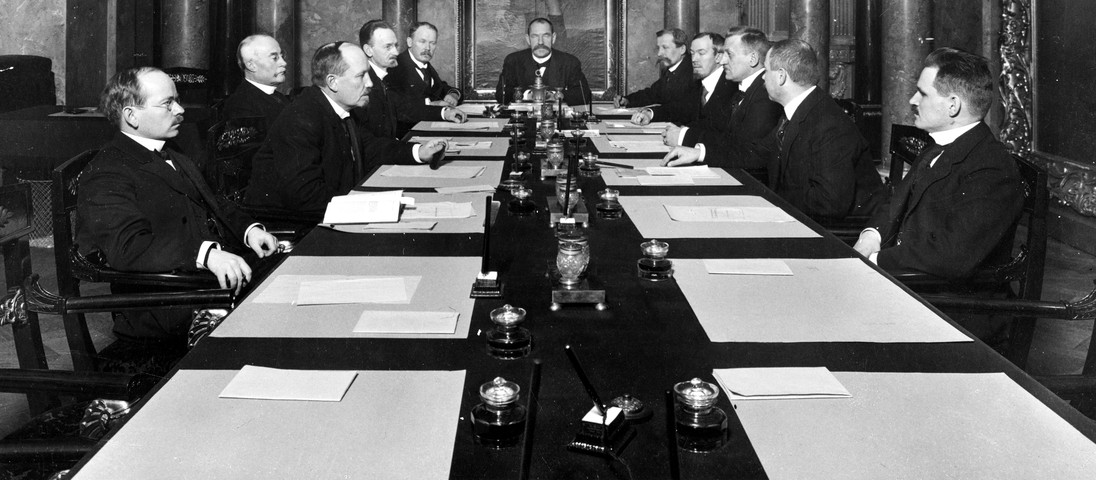

The Finnish Declaration of Independence , whose adoption by Parliament we celebrate today, shows that its authors justified the need for a new State out of the, in their view, loss of legitimacy of the old imperial Russian order. The right to do so was based, from their perspective, on the old Swedish Instrument of Government of 1772 (taken as to be still valid by Finland at the time), which allowed for the election of a new monarch in case of the extinction of the royal line, and placed the State authority on the Estates (i.e. Parliament) in the meantime2. The Declaration was explicit that “Finland’s current form of government, which is currently incompatible with the conditions, requires a complete renewal”, and clarified what form of government was to be adopted: a republic. To further support the right for the new state, the text referred to the Bolsheviks declaration of a general right of self-determination, a right that they (the Russians) should be willing to concede to the Finnish people too, “based on its centuries-old cultural development”. The declaration ends with a call to “everyone on their own behalf with rapt attention to follow the (law and) order by filling their patriotic duty, to strain all their strength for achieving the nation’s common goal in this point of time”. Independence, the common goal of the declaration, was probably the only thing that the majority of Finns agreed on. But the declaration was not going to be the culmination of the formation of an independent Finnish state, but the tense moment before the events that would shape it, including a contest for the monopoly of force. Only fifty-three days later, on the night of January 27th 1918, the Finnish Civil War started with simultaneous violent actions in the south (reds) and northwest (whites)3.

The February and the October Russian Revolutions of 19174 offered the conditions for a power vacuum that brought to the fore the already growing tensions between social democrats and the conservatives within Finland5. That is the context within which the declaration was enacted. Both factions supported the independence, yet strongly disagreed on the future of the new State. They had developed their own paramilitary units which eventually, via action and counteraction at a time when the old police had been dissolved and the new government lacked armed forces, escalated the tension into a civil war that each side saw as a war for the country’s liberation, and that we can see as an example of a fight for the monopoly of force within the Finnish territory6. Its bitter yet lasting conclusion came by a combination of events that could have ended with a very different result: the whites defeated the reds and initially agreed with Germany on a monarchy for the new state; it was only thanks to the German defeat in World War I that the “Kingdom of Finland” went from a monarchist protectorate of the German Empire 7, to the Republic of Finland, the parliamentary republic based on the Constitution of 1919.

How did this original violence, which allowed for a particular conception of the State to impose itself by eliminating the challenge to its monopoly on the use of physical force, eventually justified itself?8 Is that even possible? And if not, how was it repressed, or put to “rest”? The tensions are still present, over 100 years later9. The process of “reconciliation” is perhaps never finished, and the violence at the source only displaced, but compromises were made, the changes in workers and farmers conditions and the political pardons of the reds along with Social Democrats return to political participation allowed for the country to move forward. It is believed that what unified the country the most was the Winter War10, and what completed the process was the legalization “of the Finnish Communist Party, the building of the universal welfare state, and the art and scholarship produced about the events of 1918”11. These factors contributed to the legitimization of the Finnish State over the years12.

·•·But what about other organizations, such as the business entities, NGOs and others that make up our work environments? If inner justification (legitimacy)13 is a key component of well-functioning States, what about other types of organizations? Though it is true that businesses, religious institutos or NGOs do not exercise the same level of power over individuals or other groups14, and so do not require neither a monopoly on force nor the same “mystical foundation of authority”15 as the State, they still require legitimacy to operate. My question is, is the legitimacy expected of states, the inner justifications that make their structures and regulations acceptable by those within, so different than what should be expected of other organizations? And if so, why? How is it that most of us keep requiring that political legitimacy be founded on political and ethical values such as “level of confidence” from citizens, or the levels of openness and fairness, transparency, accountability, and representation of government16, but when it comes to other forms of organizations we seem to be OK with a very different set of requirements and practices? Perhaps we should change our legitimacy expectations for non-state actors, holding businesses, NGOs and other organizations to higher political and ethical standards, going beyond the marketing domain of SCR (Social Corporate Responsibility), DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) or ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) and into the fundamental reasons that make their existence not just bearable, but desirable?17.

Weber, Max, “Politics as a Vocation”, translated by H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, in “Essential Readings in Comparative Politics”, by Patrick H. O’Neil, Ronald Rogowski, eds., W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2013 (4th edition), p.40. ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors, “Instrument of Government (1772),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Instrument_of_Government_(1772)&oldid=1191856054 (accessed December 26, 2023). ↩︎

Maavara, Alec. “Civil War.”, Finland Divided. https://finlanddivided.wordpress.com/the-civil-war/ (accessed December 25, 2023). ↩︎

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “February Revolution”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Nov. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/February-Revolution . (Accessed 25 December 2023). ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors, “Finnish Civil War,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Finnish_Civil_War&oldid=1190886521 (accessed December 25, 2023). ↩︎

And so a battle for the State. ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors, “Kingdom of Finland (1918),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kingdom_of_Finland_(1918)&oldid=1188932676 (accessed December 26, 2023). ↩︎

It is hard to imagine the terror experienced in less than 4 months. There were over 38,000 casualties, or 1.2% of the total population of 3.2 million. 28,000 of these were reds, of which 10,000 were the result of court-martial executions and another 12,500 from the conditions of the war camps. 6,600 reds died in combat. On the white side, over 1,650 were victims of terror, and 3,900 died in combat. See Tepora, Tuomas, “Finnish Civil War 1918” , in 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.15463/ie1418.10084 (accessed December 26, 2023) ↩︎

See Civil War still divides Finland after 100 years, poll suggests , (accessed December 25, 2023). ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors, “Winter War,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Winter_War&oldid=1191580217 (accessed December 26, 2023). ↩︎

“How Finland found a road to reconciliation after the Civil War of 1918”, https://finland.fi/life-society/how-finland-found-a-road-to-reconciliation-after-the-civil-war-of-1918/ (accessed December 25, 2023) ↩︎

Cf. with the Fragile States Index for Finland (accessed December 26, 2023). Finland is ranked as the 3rd most stable state in the world, only behind Norway and Iceland, and with one of the highest marks in State Legitimacy , only behind Denmark, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Switzerland in 2022. ↩︎

Weber mentioned 3 forms of State legitimacy, “traditional”, “charismatic” and “rational”, but there are multiple others, for instance “Consent” or “Instrumentalism”, but also “Proceduralism” etc. See for example Peter, Fabienne, “Political Legitimacy”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/legitimacy/ ↩︎

To a point, the State regulates these other organizations and defines the limits of their power, so it clearly requires special attention. ↩︎

Derrida, Jaques, “Force of Law: The ‘Mystical Foundation of Authority’”, in Deconstruction and the possibility of justice, David Gray Carlson, Drucilla Cornell, and Michel Rosenfeld, eds., Routledge, New York, 1992. “Since the origin of authority, the foundation or ground, the position of the law can’t by definition rest on anything but themselves, they are themselves a violence without ground.” (p. 14). ↩︎

Cf. with the State Legitimacy Indicator description. Couldn’t these dimensions be applied to other organizations too? Not to mention the ambiguos calls for democratic process and democratic participation… ↩︎

This is more acute when we consider the power that some of these organizations have over individuals and the prevalence of harmful work cultures, as for example described in “Moral violence in organizations: Hierarchic dominance and the absence of potential space”, by Seth Allcorn and Michael Diamond, in Organisational and Social Dynamics, Phoenix Publishing House, 2004, pp. 22-45. This is here for reference with the hope to be able to come back to it in the near future. ↩︎

- [Creative Commons](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en)](/images/Swatch_Irony_angle_below_cut_hu0e3d81a6ae5693dcfe663052b48521c6_408948_548x240_fill_q90_h2_lanczos_smart1.webp)