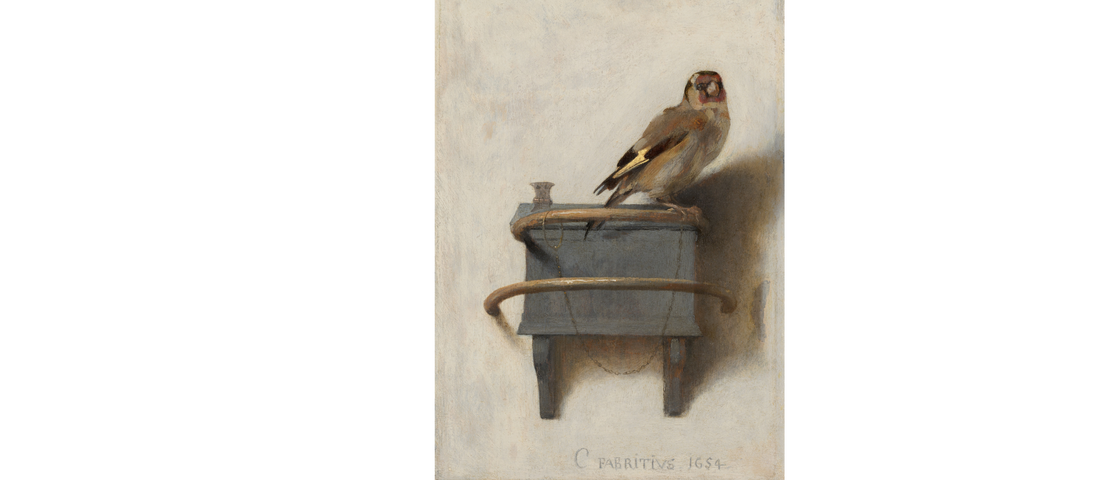

Cages or wings. Which do you prefer?

- Oscar

- Organizations , Books

- July 19, 2024

It’s been half a year since I re-launched this site. I had the intention to write more often. I guess I have (after all, I had been many years without writing prior to the relaunch!), but not as often as I wanted to. In fact, this is a far cry from my intention to write at least once a week. Being busy does not help, but neither does fear: I’ve always thought of writing as a form of exposure. If “expose” comes from putting (pose) something out (ex), the fear in writing comes from having myself (the self1) revealed, open, and so vulnerable. The more personal the writing, the more personal the exposure. From lack of post comments (a feature I will add soon) to lack of time, for the last few months I seemed to easily find good reasons not to write or publish, but eventually I needed to write, not because I have overcome my fears, but because I want to. With the exception of this paragraph, this post is not about my fears or my struggles, its topic is, however, “personal”, it matters to me. It is about our work organizations, where we spent a considerable amount of our time and energy, from the perspective of a different type of business book: Humanocracy: creating organizations as amazing as the people inside them 2

Cages or wings. Which do you prefer? Ask the birds. Fear or love, baby. Don’t say the answer. Actions speak louder than words. 3

Humanocracy: Reimagining Organizations fit for human beings

As those who have worked with me in the last few years could probably confirm, I have not missed opportunities to talk about Humanocracy. I had read Humanocracy almost by chance in early 2021. The book struck a chord at a time when we were all discussing the changes introduced by the lock-downs, the new working from home arrangements, and the tensions between the new freedoms and the old controls along the challenges with the blurred boundaries of work and non-work life. If anything, the book gave me hope: I had become increasingly disappointed with our work organizations, particularly while working at those bigger than a handful of people, and was looking for alternatives at a time that felt right to radically rethink what we were doing. I was not expecting much from the book, I just got hooked by the (sub)title, and to my surprise (was not expecting that from a business book!), I found myself, in multiple occasions, jumping from my seat with excitement as I felt reflected in the book’s own perspectives, and what is even better, read about real organizations that, unbeknown to me, were operating with these principles at various (large) scale.

·•·I had been interested in organizations for most of my adult life, yet my early experiences weren’t focused on corporations or for-profit companies but faith communities, churches, and mission organizations in the Protestant Christian tradition. I learnt very early that our organizations reflect their underlying assumption about the people that make them. Congregational, presbyterian and episcopal structures and ideas4, for example, are based on very different perspectives on human nature, God and authority, and that is reflected5 in the concrete practices that the communities identified as one or the other of these adopt. Of course they also reflect power structures, and at times one could be forgiven for thinking that the assumptions came to justify the organizational arrangements and power relations that preceded them. Either way, our anthropology both, determines our political practices and is determined by it.

The anthropological perspective that runs through Humanocracy, from the title to its principles, is fundamentally optimistic and empowering: human beings are not means or resources6. This is why, instead of looking at people as “meatware”7, the goal of the book “[…] is to lay out a blueprint for turning every job into a good job […] to redesign work environments so they elicit the everyday genius of every human being”. It is not that this perspective is problem-free. We could ask who are the “humans” here, what are their characteristics, or how this vision would enable the multiple ways (other) humans understand themselves outside our current economic model. But I still find its optimism contagious and necessary.

It was this optimism that first got me interested in the book. You can read it in the subtitle if the neologism in the title is not already revealing: “creating organizations as amazing as the people inside them”. I want to reiterate the importance of that assumption: people in our organizations are defined as amazing! They are resilient, creative, passionate. When was the last time you heard that said at the organizations you work in/with? Our beliefs about the people in our organizations or our communities are more important than we realize, and if we confront them honestly, we will need to confess that we don’t do enough to hold them, or simply admit that we are rather pessimistic about our fellow human beings 8.

This is why the first part of the book places this belief at the center and contrasts it with the state of our organizations: while people are amazing; the majority of our organizations, unfortunately, are not. In fact, most of them seem to be pretty similar:

[…] in what ways are organizations alike? What traits are common to Sony, Telefonica, UNICEF, the Catholic Church, Oracle, Volkswagen, HSBC, Britain’s National Health Service, Petromex, the University of California, Rio Tinto, Carrefour, Siemens, Pfizer, and millions of other, lesser-known organizations?

The answer: they are all bastions of bureaucracy. They all conform to the same bureaucratic blueprint:

- There is a formal hierarchy

- Power is vested in positions

- Authority trickles down

- Big leaders appoint little leaders

- Strategies and budgets are set at the top

- Central staff groups make policy and ensure compliance

- Job roles are tightly defined

- Control is achieved through oversight, rules, and sanctions

- Managers assign tasks and assess performance

- Everyone competes for promotion

- Compensation correlates with rank 9

So if the people that make up our organizations are amazing, what makes the organizations they form together sick is bureaucracy. Based on its current prevalence across the board, it might as well be declared endemic. But it is not, in spite traditional representations, a bunch of papers in an office full of people in suites with stamps in their hands. As with the list above, perhaps we need to look closer at what we have all around us: hierarchies represented as a pyramid of lines and boxes10; centralization and top-down power structures as if there was no other way to coordinate and get work done at scale11; overspecialization that in the end prevents innovation and collaboration; and its corollary, standardization, born with the intention to increase efficiency (and that they did for a time, but at what price?), yet resulting in controlitis that turns otherwise highly capable and creative people into machines12. As with all greatly feared ghosts, bureaucracy is all around us, and even if we might not (yet) see it clearly, it is at the base of the inhumanity of our organizations. Perhaps we could use a bit of help here and complete an initial assessment on the level of bureaucracy in our organizations. Thankfully the authors developed a Bureaucratic Mass Index (BMI) survey that takes into account these traits and will, I hope, help make bureaucracy around us turn (more) visible.13.

But why bureaucracy, in spite of its cost and the fact that at least most of us openly oppose it, is still so prevalent? Maybe because, like all ghosts, it haunt us. Or maybe it is its more concrete and real self-replicating nature. The problem with bureaucracy is that, to a point, it is self-imposed: not something an external force has placed on us, but what we ourselves sustain and fuel.14 That bureaucracy required the raise of a new class or role, the manager15, does not preclude the fact that current workers and managers alike are trapped in this together, all prevented from being fully human, forced into a box role and deprived from becoming their best selves16. Of course those in the bureaucratic class, having learnt the skills to play the game, are not really interested in a change now: “Asking an experienced bureaucrat to go from manager to mentor is like asking LeBron James, the star forward of the Los Angeles Lakers, to abandon basketball in favor of volleyball.” But even if the bureaucrats would not oppose, because most of us have experienced nothing else and are so used to it, imagining an alternative is hard… we might be really haunted, or simply too afraid to change, to the point that we will mock anyone who suggests that we do. I still remember this sentence from the first time I read the book. It still makes me both, laugh and almost cry:

Suggest abolishing the trappings of bureaucracy—the multiple management layers and all-powerful staff groups—and your colleagues will scoff at your naivete. What’s next? Letting people design their own jobs, choose their colleagues, and approve their own expenses? Well, yes, actually, but if you go there, heads will explode.

The book first part ends after having shown why bureaucracy needs to go. It is economically costly, and its pervasive effects, including loss of effectiveness, innovation, and flexibility, affect us at multiple levels. However, it is the moral argument, sustained by a particular vision of human beings, that resonates the most with me. If we see how wonderful (and terrible too17) we humans can be, we will deeply long for a change in the lines the book draws, and not just for ourselves18. On the contrary, if we assume “employees are looking for an excuse to be irresponsible”, that they “are incapable of exercising judgment”, or that they “are unable to think beyond their own role or unit”, we will perpetuate the bureaucratic model. This is why the authors conclude with a call to action:

·•·If we believe that a just society is one in which people have the opportunity and freedom to become their best selves, then we shouldn’t tolerate the soft tyranny that millions of employees face each day at work—what oral historian Studs Terkel called ‘a Monday through Friday kind of dying.’

The second and third parts of the book cover cases and principles. I don’t intend to discuss much of that, but I will mention a few of the things that are important to me.

First, in introducing Nucor and Haier, the book provides stories and details that show that adopting a non-bureaucratic model can be done. And no, these companies are not perfect systems, they are in a constant process of learning and improving. But as already insisted, “[w]hat makes these companies valuable as role models isn’t so much their unique practices as the distinctive belief systems that gave birth to those practices.”19

Second, since most if not all of the companies showcased in the book are different (and how could they not be unless they were more of what we already have?), the book does not intend to offer “best practices” that our cargo-cult aspirations, along the consulting-industrial complex, may easily turn into products for consumption. Instead, the book offers seven principles that would be at the core of these new non-bureaucratic forms of organization. These principles represent the ways organizations think rather than the ways they act:

When benchmarking other organizations we tend to ask, what do they do differently? But when we’re trying to make sense of a company that is different in almost every respect, we need to ask, how does it think differently?

This does not mean, of course, that we can decouple action from thinking, but that the new practices Haier, Nucor and the others exemplify are unique to their context, while their forms of organization are still emergent. Bureaucracy is also grounded on a set of principles (“stratification, standardization, specialization, and formalization”), but by their very nature they operate in a similar way and their practices are much easier to observe and identify (and sell as “best” too!). And this is also why it is much easier to define humanocracy negatively (by what it is not) than to agree on what a humanocracy should look like, or what its principles really are.20 From Ownership to Markets, Meritocracy to Community, Openness to Experimentation 21, and with each of these, a dose of Paradox, at times I found myself agreeing fully, others less, and sometimes also disagreeing with the authors22. Although not everyone would agree on all of these principles, or to the same extent, the examples of the organizations that hold or live up to them give us hope; they give me hope.

Finally, in “The Power of Paradox”, the authors point to the various tensions and choices our organizations face. The pairs growth-profitability, flexibility-scale, long term-short term, innovation-execution, creativity-discipline, speed-diligence, risk taking, prudence23, all are modes of the underlying exploit-explore tension24. But bureaucrats “abhor ambiguity”, and “bureaucracies are replication machines. They’re designed for exploit, not explore.” In the previous chapter on experimentation we had been reminded of the “law of requisite variety”25. I see a clear connection with the need for paradox: pretending to resolve this tension either way, that is, to manage the trade-offs by eliminating one of the poles, is diminishing the potential responses of our organizations to adapt and thrive in an ever changing environment, either by focusing only on the present (exploit), making the organization incapable of addressing the future, or by benefiting the future (explore) at the risk that there may not be a future at all. The need for both is sustained in the tension, yet it is clear that given the prevalence of bureaucracy and its one-sided preferences, sustaining the paradox implies a corrective action to balance out this bias while changing the mode exploit is made possible.

The most fundamental trade-off […]is between freedom and control. This tension lies at the very heart of the explore-exploit dilemma.

In a sense this is nothing new, as thousands of years of political and philosophical discussions confirm 26. The result, however, is not that freedom and control stay in tension, but that real freedom implies a form of self-control: it loses its traditional grip as something imposed from outside (or top-down), and becomes self-imposed by virtue of individual incentives (ownership) or a sense of loyalty and gratitude (community), among others. In a sense, it is freedom that takes the upper-hand, and exploit is made possible in a very different way than in a hierarchical organization.27

·•·The book’s last part is a call to “hacktivism”.28 Why do we need this mix of hackers and activists? Because our organizations are not going to change top-down: “Complex systems, like a human organism or a vibrant city, aren’t built top-down. They have to be assembled bottom-up through trial and error.” In other words, it is hopeless to use the old paradigm methods to bring about the new one. To reuse an image close to the authors, it would be as “liberating” as imposing democratic values through military intervention or coercive means. However, “[…] waiting for bureaucrats to dismantle bureaucracy is like waiting for politicians to put country ahead of party, for social media companies to defend our privacy, or for teenagers to clean their rooms. It may happen, but it’s not the way to bet.” This is why we need people who, like hackers, are not waiting for permission to solve a problem ("hackers are naturally anti-authoritarian"), and who, like activists, are aware of the need to connect with others and build a community around their cause: “A hacker builds things. An activist marshals a coalition. A hacktivist does both—she mobilizes lots of people to try new things.” 29

Of all the requirements for a hacktivist, a moral conviction on the values the book introduced on the first part, along a servant’s disposition and the courage to oppose the status quo, probably rank first. We are reminded that “the pursuit of humanocracy is inherently sacrificial”. Trying to break away from the current state of things is to venture into an (almost) unknown territory, where we risk looking bad and losing the confidence or support of the familiar, and the new modus operandi is rooted in giving up the one thing we have been told to seek in our organizations: positional power.

Perhaps there is no better quote to close my comment on the book than this:

·•·Mary Parker Follett, the early twentieth-century management guru, argued that “leadership is not defined by the exercise of power but by the capacity to increase the sense of power among those led.” As a rebuke to bureaucratic power mongers, this is nearly as radical as Christ’s proclamation that the first shall be last. It’s here we find the beating heart of humanocracy—in the selfless desire to help others accomplish more than they would have thought possible. This is the ethos behind Zhang’s vision of Haier as a squadron of dragons. It’s why Southwest Airlines celebrates a “servant’s heart.” It’s what prompts a Nucor plant manager to proclaim that “We value every single job, every single position, every single person, but being a manager is the least noble job.” If you’re a manager of any sort, you can’t empower others without surrendering some of your own positional authority.

Cages or wings. Which do you prefer? Ask the birds. Fear or love, baby. Don’t say the answer. Actions speak louder than words.

If we may use such language to describe what is being exposed here, that is. What is the self, where is it that it may be put “out there”, in writing or otherwise? ↩︎

Gary Hamel & Michele Zanini. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, Massachusetts, 2020. ↩︎

From the song “Louder Than Words” (Tick, Tick… Boom) by Jonathan Larson. Listen the full song in the version from the Netflix Film by Andrew Garfield while you read this post… ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors, “Ecclesiastical polity,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ecclesiastical_polity&oldid=1223230696 (accessed July 7, 2024). ↩︎

This “reflection” is always mediated by the concrete context in which these communities exist, and at times there is a tension between what they claim to adhere to and their actual practices. For example, and relevant to the topic, I have seen how congregational models in a Catholic-majority country live in tension with the practices and assumptions their members bring from their experiences with the larger context. This is not different than what happens with other type of organizations. ↩︎

In a bureaucracy, human beings are instruments, employed by an organization to create products and services. In a humanocracy, the organization is the instrument—it’s the vehicle human beings use to better their lives and the lives of those they serve." In another example, while discussing Haier in chapter 5, Zhang, its CEO is said to have been inspired by Immanuel Kant: “You won’t find many CEOs whose organizational philosophy gives preeminence to human dignity and agency, but if you want to build a humanocracy, that’s the only perspective you can take. ↩︎

costly machine substitutes that are incapable of being upgraded ↩︎

The extent to which someone regards a problem as important, or even acknowledges its existence, depends on their worldview—their paradigmatic beliefs. If, for example, you believe human beings have a sacred trust to be good stewards of the natural environment, you’re likely to take the threat of climate change very seriously. If, instead, you see the earth as a reservoir of resources to exploit for short-term gain, environmentalism will make little sense to you. So it is with humanocracy. If your worldview places a premium on human freedom and growth, you’ll regard the inhumanity of bureaucracy as intolerable and feel compelled to act. If, on the other hand, you regard human beings as factors of production, you’ll make excuses for bureaucracy and be content with minor reforms. Your worldview matters—a lot. Yet as a rule, most of us spend a lot more time thinking about practices than principles. That, as much as anything, explains why we’re stuck. ↩︎

Chapter 1. Now, let’s go and check that list against the organizations we have worked for. How many of these would you check? Most likely a few. No, bureaucracy is not a pile of papers on a desk, it’s an all too familiar model for control that has gotten very effective over time as technology has evolved: “Rather than replace top-down structures, technology is more likely to reinforce them. Digital technology allows jobs to be sliced into ever-smaller segments and outsourced to the lowest bidder, further dumbing down work. Real-time analytics make it possible to assess job performance minute by minute—catnip to control-obsessed managers.” ↩︎

The org chart is another bureaucratic device that has been around for over 100 years. Another book I hope to cover in a future post is Brave New Work, by Aaron Dignan. As an advance, have a look at his explanation on the origins of the org chart (The Org Chart is Dead ) ↩︎

The tendency to postulate the need for central (and hierarchical) models to deal with complex phenomena is what Mitchel Resnick calls the Centralized Mindset: “Most people seem to have strong attachments to centralized ways of thinking. When people see patterns in the world (like a flock of birds), they generally assume that there is some type of centralized control (a leader of the flock).”. Resnick, Mitchel. 1996. “Beyond the Centralized Mindset.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 5 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0501_1. ↩︎

Standardization sets a floor on acceptable behavior, but it often sets a cap as well. Machines only do what they’re told. Our organizations will never be fully capable until we rid them of “controlitis. ↩︎

I’ve looked back into my career to get a sense of what BMI scores I’d get by providing the answers based on the different teams and orgs I worked in in the past, and I never scored enough to be in the green, with only one occasion in the yellow middle (36)… The book confirms I am not alone: “We scored each of the BMI questions on a scale of zero to ten, where zero denotes the complete absence of bureaucracy-related traits and ten a high degree of bureaucratic drag. Adding these results together, we calculated an overall BMI score for each respondent, ranging from zero to a hundred. The average score across the survey was sixty-five.” ↩︎

The fuel that feeds the growth of bureaucracy is the quest for personal power. Power brings survival advantages, and we are wired to seek it. Having the power to direct your life is essential, but like the desire for food, alcohol, or sex, the lust for power can enslave us. That’s why philosophers and moral teachers so often warn us of its dangers. ↩︎

“In standardizing work, Taylor created both the demand function and the job description for a new class of workplace demi-czars. It was the manager’s job to ensure that rules were followed, variances were minimized, quotas were filled, and slackers were punished. And so it is today. Look up the verb form of the word “manage” in any thesaurus and the first synonym is likely to be “control.” You might be tempted to believe that twenty-first-century organizations have moved beyond this obsession with control, but you’d be wrong.” (Chapter 2)

I would add, look up the etymology of “manager” and see its relation to hand (handling) or the more negative relation it has to manipulation. ↩︎In most organizations I have been to, the manager track implies better pay and more power than the euphemistically called “individual contributor” roles, which has lured many great experts into seeking manager positions, leaving their true passion in their area of expertise for better pay or for (the hope to have) a say on the conditions that they and their colleagues carry out work. ↩︎

I hope to be able to come back to this in the future, as Sophocles, Antigone’s has it: “Wonders / terrors [deina, pl.] are many, and none is more wonderful / terrible [deinon] than man.” trans. R. C. Jebb, rev. Pierre Habel and Gregory Nagy, newly rev. by the Hour 25 Antigone Team (Brian Prescott-Decie, Jacqui Donlon, Jessica Eichelburg, Claudia Filos, Sarah Scott) (Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University), https://chs.harvard.edu/primary-source/sophocles-antigone/ (accessed July 7, 2024). ↩︎

This reminded me the Global Leadership Society website’s Home page top picture, where a protester is holding a banner with the legend “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention”. This, again, is a reminder for another post. ↩︎

True to the spirit of humanocracy, Nucor’s model isn’t about pushing employees to do more, but giving them the opportunity to be more—more than blue-collar workers, more than order takers, more than mere operators, more than employees. Nucor’s frontline team members are experts, innovators, risk takers, and owners. Nucor proves unequivocally that every job can be a good job, whatever the industry. ↩︎

That the authors take as an example democracy ("While political systems in mature democracies differ in their particulars (Britain, unlike the United States, lacks a written constitution), they’re all grounded in the same corpus of pro-democracy principles.”) is perhaps symptomatic of the challenge we have with humanocracy too: we may lack an agreement of what its principles are, many of which require a particular worldview too… ↩︎

For these first six principles, the authors have a matrix table available as PDF here ↩︎

For instance, I could agree on most of what was written on ownership, or support the practice of crowdsourcing strategy in a company, but have issues with leaving other (i.e. moral) decisions to markets (there is no such a thing as a completely free market, all markets have rules/regulations, and whoever sets the rules has an advantage) or I am wary of meritocracy (particularly in the form defined in Ray Dalio’s Principles, a book I loved and struggled with in equal measure). ↩︎

FIGURE 13-1. ↩︎

Decades ago, James March, the organizational theorist and Noble Prize winner, argued that the most basic problem for any organization was to “engage in sufficient exploitation to ensure its current viability and, at the same time, devote enough energy to exploration to ensure its future viability.” ↩︎

The law states that for a system to remain viable, it must be capable of generating a range of responses as diverse as the challenges posed by its environment. As Ashby put it, “Only variety can absorb variety.” ↩︎

Though the notion of autonomy has been used in politics since the Greeks, Kant used it to refer to individuals, and also introduced its opposite, heteronomy. It would be interesting to explore the relation between freedom and control in this chapter from the perspective of Kant’s motion of autonomy as reconciling self-determination with a universal law. ↩︎

In a humanocracy, control comes from a shared commitment to excellence, from accountability to peers and customers, and from loyalty to an organization that treats you with dignity. In the first case, you end up with Weber’s “iron cage”; in the second, an energized workplace where high autonomy and high accountability are mutually reinforcing. ↩︎

A hacker builds things. An activist marshals a coalition. A hacktivist does both—she mobilizes lots of people to try new things. ↩︎

In a nutshell, for the authors: a hacker is someone who takes the initiative in addressing a problem, and acting as if they have permission (whether they do or not) to take a stab at it, focused on solving it through experimentation for as long as it take to do so; and activist is a mobilizer, someone whose credibility, courage, contrarian thinking, compassion and connections enable them to bring people together around an issue and eventually create a movement. ↩︎

- [Creative Commons](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en)](/images/Swatch_Irony_angle_below_cut_hu0e3d81a6ae5693dcfe663052b48521c6_408948_548x240_fill_q90_h2_lanczos_smart1.webp)